The Brazilian Proletariat

Today, it’s estimated that around 90% of the Brazilian population lives in what the State considers cities, with 17 cities of more than a million of people each[1]The State’s statistics consider any house conglomeration as an urban area and not countryside. Brazil has 5,600 cities, and 80% of them have populations of under 15,000, with most under 10,000, an … Continue reading. The rural exodus that started in the 60s only accelerated after the end of the military regime in 1985. This article describes the formation of the Brazilian proletariat and its evolution to current times.

1. Slaves, Migrants and Proletarians

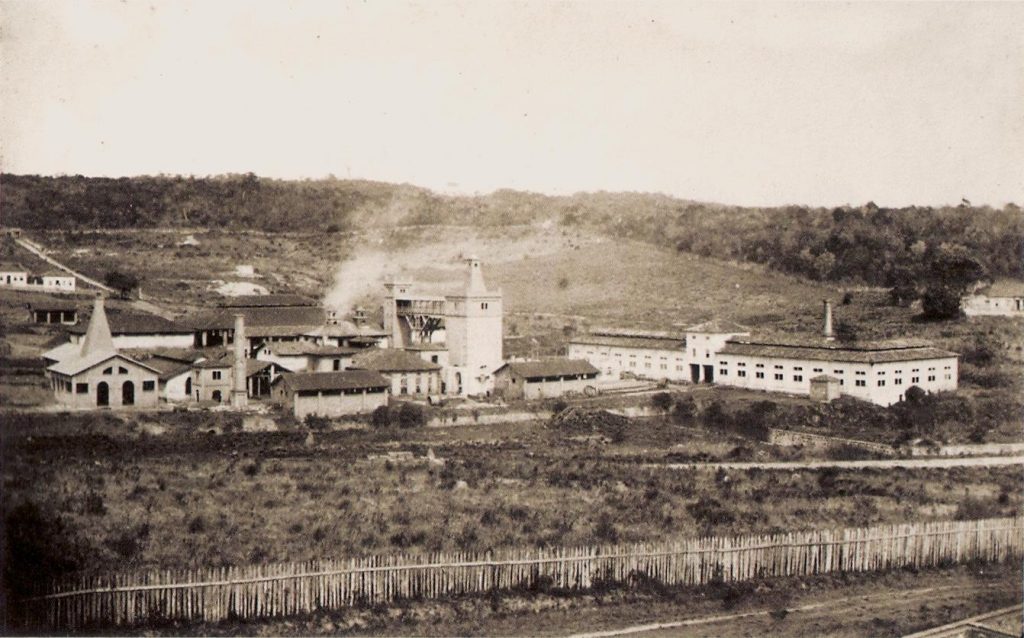

Slavery in Brazil was established at the onset of the Portuguese colonization in 1500 and lasted until 1888, a year before the formation of the First Brazilian Republic. At that time, there was an estimated 1.5 million slaves who became the main source of the formation of the proletarian class, as they were already the one’s working in factories and construction on such major projects as the construction of the first railways, urban mass transportation and electricity system starting from the 1850s.

Therefore, the abolition of slavery (called the “Golden Law”) did not impact the economy of Brazil, and provided the first workers that the growing number of factories needed. The number of factories grew quickly, going from 600 in 1889, to 7,000 in 1914 and over 13,000 in 1920. Another source of the formation of the proletariat were the migrants, mostly Italian and Spanish, who started to arrive in the country since the mid of 19th century came to Brazil in the beginning of the 20th century.

Therefore, the abolition of slavery (called the “Golden Law”) did not impact the economy of Brazil, and provided the first workers that the growing number of factories needed. The number of factories grew quickly, going from 600 in 1889, to 7,000 in 1914 and over 13,000 in 1920. Another source of the formation of the proletariat were the migrants, mostly Italian and Spanish, who started to arrive in the country since the mid of 19th century came to Brazil in the beginning of the 20th century.

The first strikes and embryos of unions can be traced to as far as the middle of the 19th century, but the workers’ movement really developed after 1917 when a general strike against food and fuel cost increases paralyzed the country’s industry. Later, two events strongly influenced the workers’ movement: the news of the Russian Revolution, and the formation of the Communist Party of Brazil (PCB) in March 1920.

The anarco-unionist past of the majority of its founders led to the PCB analysis of “industrialism v. agrarianism” as the principal contradiction of the country. This resulted in the false understanding that British imperialism, which was based in the latifundio, was against the industrialization and that North American imperialism was more be favorable. In their political plan, the PCB adopted the opportunist electioneering line of the BOC (Worker Peasant Block). After the Comintern’s criticism, the Party abandoned this line and formulated the anti-imperialist and anti-fascist united front, promoting the class trade union activity with which it would gain the support of the majority of the main trade unions at the time (dockers, railroaders, miners and weavers). The Great Depression impacted the fragile economy and heightened the political crisis of the republic of rural oligarchies. This resulted in conditions that led to an armed movement led by Vargas (former minister of economy of the government and defeated candidate in the elections) seized power and installed a corporativist fascist regime for fifteen years. The PCB mobilized the trade unions against this regime in an antifascist united front as part of the Tenentismo (rebel soldiers), the petit and medium bourgeoisie. However, the peasants were not mobilized, which led to the defeat of the People’s Uprising in 1935.

The Vargas regime passed a series of reforms, such as the eight-hour workday and legal recognition of the trade-unions and created a Minister of Labor, with the goal of corporatizing the masses and preparing the field for the development of bureaucratic capitalism in Brazil. Some of the most combative unions were founded during those years, including the Trade Union of Civil Construction Workers of Belo Horizonte (STIC-BH) in 1933.

The Vargas regime succeeded in dividing the workers’ movement between the “moderate” (i.e. yellow) unions, which collaborated with the Minister of Labor, and the “communist,” which saw many of its leaders arrested. Following the end of the Second World War, Vargas was deposed by a military coup, and General Eurico Dutra, a trusted man of the USA, was elected president. Although the Minister of Labor continued to play the same role, the unions became more independent, allowing the PCB to play a larger role in their radicalization, leading to an intensification of the worker and peasant struggle. The attempts to reform the regime with a new constitution in 1946 changed nothing in the corporative structure of the State. The failure of the regime’s economic policy sharpened contradictions among the fractions of the big bourgeoisie and landlords and between them and the masses. The result was the reinstatement of Vargas in the 1951 elections as a “democratically” elected president with a populist and nationalist discourse.

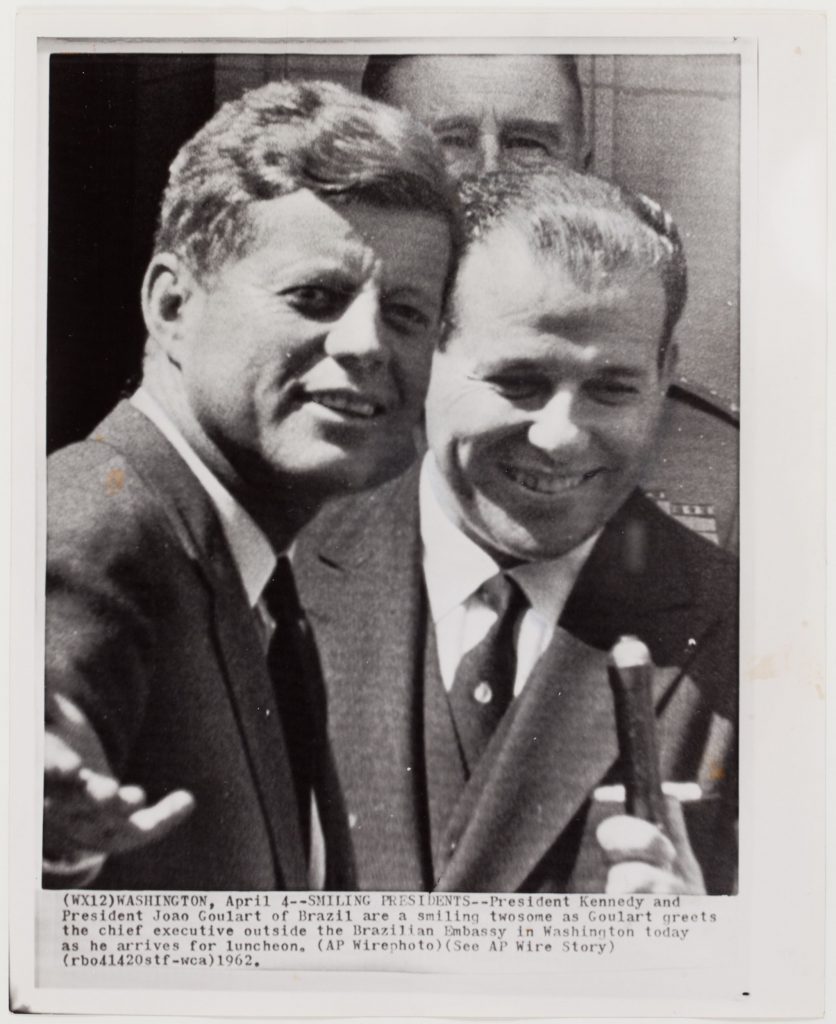

Rather than trying to overtly crush the workers’ movement with repression, the Vargas regime adopted a tactic of trying to co-opt and pacify its leaders with a series of “pro-people” reforms and programs for the nationalization and state monopoly of oil and electricity. The PCB defended the regime’s tactics and mobilized the trade unions in the popular pro-Vargas campaign. But Vargas’ main instrument to coopt the masses was betting on his Minister of Labor Joao Goulart, a representative of the national bourgeoisie of his Party. One of the reforms was to double the minimum wage, from 1,200 to 2,400 cruzeiros in 1954. While the reform was touted as a revolutionary measure, it was actually an adjustment for the steep inflation that the cruzeiro had experienced since the 1950s.

In 1958 the revolutionary struggle in Brazil was impacted by the PCB’s strategy shift towards the right, toward Khrushchev’s line of “peaceful transition” and the defense of the theory of productive forces. This led to a split between the revisionists and the revolutionaries in 1962. While the countryside stayed mostly in the hands of the revolutionaries who radicalized the peasant movement by reintroducing the idea of the necessity of armed struggle, the cities stayed in the revisionist PCB’s hands. Their change in strategy led to the pacification of the workers’ movement as the PCB became primarily focused on a path to legalize their Party.

The military coup of 1964 took place mostly because imperialists and dominant classes feared the increasing resistance and opposition in the countryside. It was a direct blow at the Peasant Leagues who were preparing the peasant struggle for land through armed struggle. The military regime brutally repressed the revolutionary and democratic organizations by arresting, torturing, murdering and disappearing hundreds of fighters. The State banned demonstrations and the rights of organization to strike. Within the worker struggle, the revolutionary leadership managed to organize only two strikes that were nevertheless important strikes against the fascist military regime in 1968: the Cobrasma Ironworks strike in Osasco-SP and the Mannesmann Ironworks strike in Contagem-MG, which forced the governement to raise the wages of all workers by 10%.

2. New Unionism & New Opportunists

Due to the populist regimes and mainly because of the actions of Goulart, Vargas’ Minister of Labor, unionism in Brazil was always dependent on the government’s political agenda. With the military coup of 1964 that deposed Goulart, the military regime forbade the right to strike, but as it began weakening at the end of the 70s, this measure became harder and harder to enforce. A decree was promulgated in August 1978 that allowed finally the right to strike, under the conditions that those strikes would not include any “essential sectors,” and were non-violent, non-political and non-ideological. This decree provided the possibility for the re-seizure of the leadership of the trade unions through elections and to strengthen the struggle for the right of union organization and the end of the control by the Minister of Labor.

Between 1978 and 1982, strikes erupted all over Brazil with workers demanding better wages, a reduction in unemployment, and for “re-democratization,” frustrating the struggle for the revolutionary overthrow of the fascist regime. The fall of the military regime was because its government was unable to solve its economic problems (skyrocketing inflation, recession and unemployment), which politically divided the dominant classes and sharpened the internal struggle within the regime, as well the growing people’s protest. New political actors appeared at this time, each trying to take advantage of the strikes to form the mass base for their future political parties.

Taking the leadership of the strikes by winning the workers with reformist promises, the different political actors limited the strikes to the boundaries of the August 1978 decree; they were conscious that the regime knew about their role and could repress them if they went too far. In general, their role was to pacify the masses precisely at the moment when the general conditions were ripe to advance the struggle.

Taking the leadership of the strikes by winning the workers with reformist promises, the different political actors limited the strikes to the boundaries of the August 1978 decree; they were conscious that the regime knew about their role and could repress them if they went too far. In general, their role was to pacify the masses precisely at the moment when the general conditions were ripe to advance the struggle.

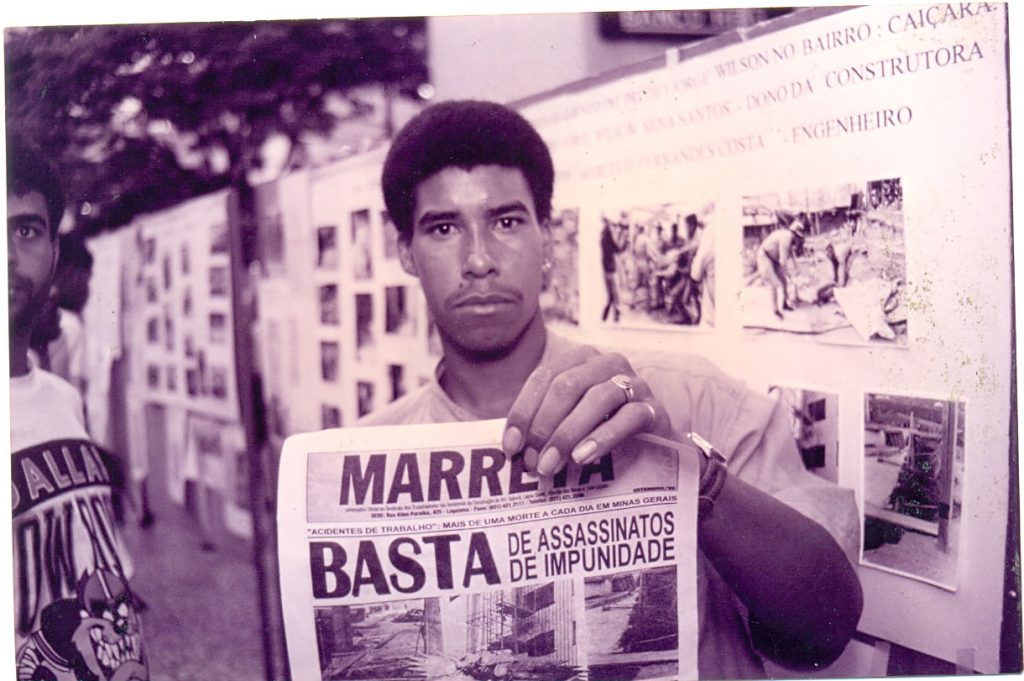

But this was not the case in all the strikes. In May 1979, workers went on strike at the Mannesmann Ironworks, a German ironwork with 14,000 workers in the industrial center of Contagem metropolitan region of Belo Horizonte-MG. This strike was organized by a group of revolutionary workers from various professions in a new formation named Marreta (Sledgehammer). Although the strike was repressed, it raised the banner of the revolutionary overthrow of the military regime. In a few days’ time, the same group mobilized civil construction workers in a strike of more than 40,000 workers in Belo Horizonte, a strike that became known as the “Revolt of the Masons,” which began with bread-and-butter demands. These strikes, together with the strike of public education teachers in the state, soon spread to all the other professions. During the construction worker strike, worker Orocílio Martins Gonçalves was murdered shot by the police. Enraged, the masses swept the repressive troops of the state away from the city center. Eventually the rebellion controlled the entire center of the state capital. Desperate, the ruling classes and authorities of the military regime sponsored a trip of domesticated trade unionists to divide the masses and end the strike. Luiz Inácio, Lula, was the main leader saying that there were groups of professional agitators trying to take advantage of the workers. His maneuvers led to the division and the economic defeat of the strike.

The Mannesmann metallurgy workers strike lasted eight days and the civil construction workers strike lasted five days. These strikes served as a formative lesson for the workers of Belo Horizonte; they were combative class struggles that resounded with the popular masses and served to politicize hundreds of new worker militants into the revolutionary ranks of Marreta. In particular, the civil construction workers managed to retake the union by expelling the patron and military regime agents.

The Mannesmann metallurgy workers strike lasted eight days and the civil construction workers strike lasted five days. These strikes served as a formative lesson for the workers of Belo Horizonte; they were combative class struggles that resounded with the popular masses and served to politicize hundreds of new worker militants into the revolutionary ranks of Marreta. In particular, the civil construction workers managed to retake the union by expelling the patron and military regime agents.

From 1981 to 1983, a series of national meetings were conducted in order to form a national confederation to unite the different unions under the direction of the new leadership that emerged all over the country following so many strikes. However, the congress of more than 10,000 delegates from the whole country, was divided by the opportunism of the unionists trained in Yankee institutions (IIADESIL, from AFL-CIO) with Lula at their head, together with Trotskyist organizations, and sectors of the catholic church. They quit the Congress and created the United Central of the Workers (CUT) in August 1983. The majority of the trade unions that struggled for unity on a class line reconstructed the General Confederation of the Workers (CGT). Marreta took part in the General Confederation of Workers (CGT) in order to advance a revolutionary line, winning many unions such as the Union of the Drivers of Passenger Transportation in 1990.

But the situation in the country demanded to continued advancement and the contradictions within the CGT led to many splits. As the struggle in the countryside became increasingly violent, particularly with the struggle in Rondonia and the Battle of Santa Elina, discussions on forming a class-based organization gave birth to the Worker and Peasant League (LOC) on September 2, 1995. The LOC was a decisive force to mobilize the worker unions in the cities to support the peasants in their struggle for land. With the further development of the peasant movement, the LOC separated into two allied organizations: the LO and the LCP.

3. Breaking with Old Ideas

The LO’s formation wasn’t simply a question of breaking from an organization to build an identical one with an “uncorrupt” leadership. There was a necessity to not only get rid of the opportunists, but also get rid of old ideas and concepts of struggle that were deeply rooted in the workers’ movement.

Besides strikes for better work conditions such as security on worksite, they identified the need to build an alliance with the peasants, seen as the main strength of the revolution in their semi-feudal semi-colonial country. While the CUT/CGT (and others that emerged from new splits like Força Sindical) leadership had no interest in that struggle, seen as too distant from the cities and without relevance, the LO sent their members to strengthen and support the resistance whenever possible.

Additionally, the LO saw the importance of not only struggling in the workplace, but also of where the workers lived. Because the League had a strong base in civil construction workers, they were able to address a direct need of the people: housing. In 1995, a Belo Horizonte neighborhood was built from the fierce struggle for land seizure and named “Vila Corumbiara” to honor to the struggle of Santa Elina. In 1999, another neighborhood called “Vila Bandeira Vermelha” was built in Betim, a city in the Belo Horizonte suburbs.

Both of the initiatives were repressed by the local authorities. Just as the struggle of Vila Corumbiara in Belo Horizonte was repressed by the PT mayor, Patrus Ananias, in Betim, the repression was ordered by mayor Jesus Lima, also a member of the PT, and led to the months-long resistance against the military police’s attempts at eviction, where two workers (Elder and Erionides) were murdered.

While the LO was building houses to serve the people, the PT became hegemonic in the CUT and turned it into an instrument to solely serve its electoral ambitions. The 1990s mark the triumph of “neoliberalism” in Brazil, brought as a “solution” to the various crises the country was going through. During his 2002 election campaign, Lula denounced the “bankers” and the IMF for being the cause of the inflation and promised to refuse to pay the foreign debt unless a careful audit was conducted to adjust the amount. However, this promise worried imperialist investors, and Lula was aware that he could not win the elections without their support, so he published an open letter stating that he wouldn’t cancel any of the unequal treaties once elected. Unsurprisingly, Lula was elected.

Lula kept his promises: none of the unequal treaties were canceled, not even the IMF agreements that obliged to pay the totality of its foreign debt, including the exorbitant interest it accrued. To make that possible, he said that austerity measures were necessary: a few months after beginning his term, Lula brought forward “labor reforms” regarding social security and retirement of the public servants, with the regularization of temporary work and “pejotização” (derived from PJ, meaning Legal Person, a form of contract in which the employer contracts the worker as a service provider without legal rights of workers workers), making them inaccessible to the poorest. The worker movement had all the reasons to protest the reforms, as their members were the most impacted, but the CUT called to calm them, assuring their members that the reforms were just “temporary measures” to reimburse the national debt in order to become independent from the International Monetary Fund (IMF) more quickly.

This type of tactic kept Lula in power from 2003 to the end of his second term in 2010. The “public-private partnerships,” the introduction of new agribusinesses and large multinational companies and the increased plunder of natural resources were all measures to supposedly help the Brazilian economy grow. While before his election Lula gave rousing speeches about how that kind of growth only profited imperialism, after he took office they suddenly showed that this was now the way to make Brazil independent.

This type of tactic kept Lula in power from 2003 to the end of his second term in 2010. The “public-private partnerships,” the introduction of new agribusinesses and large multinational companies and the increased plunder of natural resources were all measures to supposedly help the Brazilian economy grow. While before his election Lula gave rousing speeches about how that kind of growth only profited imperialism, after he took office they suddenly showed that this was now the way to make Brazil independent.

LO continued its struggle in those years. In 2003, it called for demonstrations to protest the “Lula-IMF government reforms,” and was joined by grassroots workers from other unions who didn’t buy the illusion of the “necessity for temporary measures.” During Lula’s tenure (2003-2010) and his successor Dilma Rousseff (2010-2016), the LO called for many demonstrations to protest the different reforms of the opportunist government, which brought thousands to the streets in the big cities (for example, the big demonstrations of 2006, 2007 and 2008 in the capital).

The LO organized for militant strikes, such as calling for general strikes, which had been abandoned at the end of the strikes in the 70s. The Education Workers Class Movement (MOCLATE), a union allied with the LO, also initiated occupations of schools, turning the schools into People’s Assemblies together with the parents of the students and other sectors of the community to discuss social problems and combat opportunists who used the strikes to promote candidates for the following elections.

Chasing economic growth earned the PT support from both the petit bourgeoisie and the dominant classes, but it has made it less and less popular in the eyes of the workers and peasants through years. By applying the programs of “compensatory policies” prescribed by the World Bank, “assistance” programs and the corporatization of the miserable masses, such as “Bolsa Família” and access to easy credit, they got the support of some of these masses. Through their tricks, they were able to temporarily obscure, for some, the grave economic crisis of bureaucratic capitalism. However, in June 2013, violent protests exploded in the capitals and biggest cities of the country against the headquarters of executive power, legislation offices, judiciary power, bank agencies, arrests and processes. The demonstrations continued until 2014.

Chasing economic growth earned the PT support from both the petit bourgeoisie and the dominant classes, but it has made it less and less popular in the eyes of the workers and peasants through years. By applying the programs of “compensatory policies” prescribed by the World Bank, “assistance” programs and the corporatization of the miserable masses, such as “Bolsa Família” and access to easy credit, they got the support of some of these masses. Through their tricks, they were able to temporarily obscure, for some, the grave economic crisis of bureaucratic capitalism. However, in June 2013, violent protests exploded in the capitals and biggest cities of the country against the headquarters of executive power, legislation offices, judiciary power, bank agencies, arrests and processes. The demonstrations continued until 2014.

North American imperialism with their generals in command of the reactionary armed forces saw these ongoing protests as a danger of potential revolution and set in motion a preventative counterrevolutionary offensive against the uprising of the masses. They launched “Operation Lava-Jato” against corruption taking advantage of the scandals of the PT administration. When the crisis exploded into a recession and unemployment, the struggle between the ruling classes fractions were aggravated and the PT was discarded with the impeachment of Dilma. The political and moral crises of the entire old political system was heightened, and the “politicians” and institutions of the old State lost credibility and legitimacy, leading the masses to boycott the sham elections more than ever. The Brazilian people have seen that in the last 40 years the rule of the governments of all official parties means that they are part of the exploited classes all the same.

The corruption scandal and the impeachment of Dilma Rousseff in 2015 signaled the end of the masses’ trust in the PT, with a record unpopularity and non-trust in the government (estimated at 9%). In the following elections, many saw the fascist Bolsonaro as the “lesser evil.”

4. Bolsonaro Harvested what Lula Sowed

In December 2015, while the union leadership coopted by the opportunist governments were unsuccessfully engaged to appeal to the workers to demonstrate against the impeachment, the LO held meetings between different combative unions. This first step in calling for a broader unity has been particularly important after Bolsonaro’s election, in the struggle for a General Strike of National Resistance against his “reforms” dictated by Yankee imperialism and in defense of public and free education, combined with the struggle of the poor peasants against eviction and more seizures of land.

In December 2015, while the union leadership coopted by the opportunist governments were unsuccessfully engaged to appeal to the workers to demonstrate against the impeachment, the LO held meetings between different combative unions. This first step in calling for a broader unity has been particularly important after Bolsonaro’s election, in the struggle for a General Strike of National Resistance against his “reforms” dictated by Yankee imperialism and in defense of public and free education, combined with the struggle of the poor peasants against eviction and more seizures of land.

Contrary to Lula/Rousseff, Bolsonaro has not hidden his agenda, which is a step further than the PT’s: less interventionism of the state in economy, fewer taxes (for the rich), more privatization. This isn’t a “break” from the PT government’s politics; it would not have been possible without the Lula/Rousseff reforms.

In June 2019, a general strike paralyzed the country, with an estimate of 45 million strikers. This strike contested measures of the Bolsonaro government—mostly the pension reform that increased the age of retirement from 60 to 62 in the cities and from 55 to 60 in the countryside and the cuts in education. The League participated and led these strikes in some cities such as Belo Horizonte.

In June 2019, a general strike paralyzed the country, with an estimate of 45 million strikers. This strike contested measures of the Bolsonaro government—mostly the pension reform that increased the age of retirement from 60 to 62 in the cities and from 55 to 60 in the countryside and the cuts in education. The League participated and led these strikes in some cities such as Belo Horizonte.

Bolsonaro’s plans for Brazil are militarization and the banning of people’s struggles, both in the cities and in the countryside and its sale to imperialists. After more than one year of government, Bolsonaro has shown himself to be a fascist braggart who dreams of resurrecting the military regime. However, the control of the government is really by the military generals who are leading the counterrevolutionary offensive and concentrating power in the executive. They are doing so through reforms of the current constitution, because they fear that the direct installation of a military regime that Bolsonaro wants would be disastrous and lead to a contrary-wide front. A strong resistance against his regime will be possible only with the unity of the workers and peasants: the Workers’ League’s line since its founding.

References

Revolutionary sources

- Viva os 39 anos da “Revolta dos Pedreiros” de 1979 em Belo Horizonte!, STIC-BH, 2018

- 78 anos de fundacao de Sindicato, Viva os 22 anos da retomada pelos operarios da Marreta, Marreta, 2011

- Propostas de Organizacao do Trabalho Sindical, Marreta

- Problemas da historia do Partido Comunista do Brasil, August 2016

Other sources

- The Brazilian Economy, Growth and Development, Werner Baer, 2008

- Labor and Dictatorship in Brazil: A Historiographical Review, Paulo Fontes, Larissa R. Correa, 2018

- Unions and the Economic Performance of Brazilian Establishments, 2002

- Foreign Labor Trends Report – Brazil, US Department of Labor, 2002

References

| ↑1 | The State’s statistics consider any house conglomeration as an urban area and not countryside. Brazil has 5,600 cities, and 80% of them have populations of under 15,000, with most under 10,000, an about a thousand cities with under 5,000. These are in reality “rural cities,” because the inhabitants subsist as peasants. Apart from the people living in the major metropolises, only the rich peasants (farmers) and the agrarian bourgeoisie do not live in the countryside. The villages have always existed in the countryside, but the State, because of the local oligarchies’ interests in political domination promotes villages into cities in the archives. Additionally, the urban territorial tax is much lower than the rural one, which makes it in the economic interests of landowners around the cities to register their lands as urban land rather than rural. |

|---|