Devin Zane Shaw: From German Communist Antifascism to a Contemporary United Front

The following essay was written by Devin Zane Shaw, author of Philosophy of Antifascism: Punching Nazis and Fighting White Supremacy, and is the introduction to an incoming book of Foreign Languages Press The German Communist Resistance of T. Derbent.

From German Communist Antifascism to a Contemporary United Front

Devin Zane Shaw

Reconstructing a Communist Antifascist History

T. Derbent is a communist theorist of military strategy, whose research and writing focus on the influence of Clausewitz’s theories on revolutionary thought. His Categories of Revolutionary Military Policy (Kersplebedeb, 2006) already circulates within militant circles due to its concise taxonomy of different types of revolutionary struggle. Soon two other works will join that work and the present volume in English translation, to be published by Foreign Languages Press: Clausewitz et la guerre Populaire (2004) and De Foucault aux Brigades rouges: misère du retournement de la formule de Clausewitz (2018).

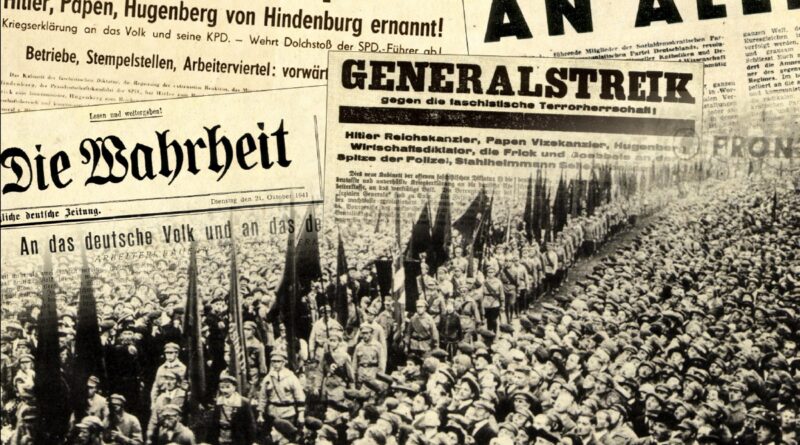

The German Communist Resistance 1933–1945 is to some degree an outlier in Derbent’s work, if not a detour. It was first published in 2008 and then reprinted in 2012 with the addition of two interviews with the author as appendices. In those interviews, he explains how he discovered unpublished archival materials documenting widespread clandestine resistance on the part of the German Communist Party (KPD), which is typically minimized or omitted from Western historiography. After failing to persuade others to follow up on this line of research, Derbent finally decided to take on the project himself, thus correcting a glaring historical omission in Western historiography—including antifascist historiography, no less—of the history of German communist resistance in Nazi Germany.

In broad outline, the received history of Nazi Germany holds that Nazi repression of socialist and communist opposition was swift. The main Communist Party leaders were arrested and detained in concentration camps while many thousands of cadres went into exile to fight fascism from abroad. A viable resistance only begins in the late 1930s, organized by anti-Hitler factions of the bourgeoisie and aristocracy (the Kreisau Circle or their “heirs,” the conspirators who carried out an assassination attempt on Hitler on July 20, 1944) or among small networks of heroic dissidents such as the White Rose group (whose best-known members are Hans and Sophie Scholl). Communist resistance is not entirely omitted from this received history, but it is said to re-enter near the end of the war and it is grouped with socialist and Christian resistance. However, grouping these forms of resistance together is, in Derbent’s terms, a “sham”: Christian and socialist resistance was carried out by individuals or small networks; by comparison,

only the communist resistance embraced all possible forms of struggle (propaganda, sabotage, guerrilla warfare, espionage, union struggle, etc.). It is the only one to have fought from the first to the last day of the Third Reich, and to have extended its action to the whole of Germany (even in the camps and in the army). Finally, it is the only one to have really weakened the Nazi war machine.

Furthermore, although antifascist historiography acknowledges the role that the KPD played in numerous antifascist organizations, such as Antifaschistische Aktion, the discussion typically ends where Derbent’s account takes off, with the Nazi repression of the Communist Party in 1933. While clandestine work lacks the organizing capacity that open resistance has available to it, that does not nullify its impacts. The reader notes a certain amount of repetition as repression fails to stop resistance: KPD organizations carry out clandestine action, they are dismantled by the Gestapo, dozens if not hundreds of militants are rounded up and imprisoned or executed, the organizations are reconstituted and return to action. In the midst of this repression, communist resistance carried out propaganda campaigns, supported strikes and sabotage of the war industry, and organized resistance in the army and in concentration camps. Derbent also catalogues communist involvement in exile, in the Spanish Civil War and in other occupied countries.

Derbent’s short intervention is admittedly not exhaustive; it only aims to give a representative picture of the scope and importance of communist resistance. By focusing almost exclusively on the KPD, he shows that the communist resistance followed in practice a remarkably consistent clandestine policy of opposition to Nazism even as the Soviet Union’s and Comintern’s political line shifts over time. Indeed, Derbent presents some evidence that the Soviet-aligned militants of the KPD continued to carry out clandestine actions against the Nazis during the period of the nonaggression pact between Germany and the Soviet Union. I would conclude on this basis that when Derbent contends that German communist resistance maintained a continuous opposition to Nazism, this continuity was one of military policy rather than political policy, a continuity that is perhaps legible only when we focus, as Derbent’s analysis frequently does, on the former rather than the latter. There’s a relationship between the two that Derbent could have developed further.1

In any case, the clandestine resistance he describes dwarfs that of the individuals and groups typically celebrated in popular Western historiography; and yet, today the reader will be surprised to discover the quantity of munitions and planes rendered inoperable by communist sabotage. These historical omissions are the result of a Western, anti-communist political consensus, which continues to treat communism and fascism two sides of the same totalitarian coin. And yet, today just as yesterday, supposedly liberal and progressive but anticommunist blocs attempt to make peace with far-right and fascistic political tendencies in order to shore up capitalist hegemony.

* * *

Antifascist historiography, at least in the English-speaking world, tends to date the emergence of modern militant antifascism around 1946 with the formation of the 43 Group in England.2 The 43 Group, which was comprised mainly, but not exclusively, of Jewish veterans of World War II, used physical confrontation to break up public meetings and rallies of a variety of fascist groups. They used direct action to undermine fascist organizing because the typical liberal mechanisms of social mediation—a combination of the inculcation of liberal norms, the so-called marketplace of ideas, and law enforcement—do not. Indeed, liberal norms and legislation tend to permit far-right or fascist organizing on the basis of freedom of speech and association while police are sympathetic to far-right groups for a variety of reasons, reasons we will return to below. In light of the failures of liberal mechanisms to halt fascist organizing, the 43 Group carried out its actions as a form of “communal defense.”3 M. Testa summarizes this period of antifascist struggle in terms which are contemporary enough: “militant anti-fascists found themselves in a ‘three-cornered fight’ against both fascists and the police… anti-fascists were statistically three times more likely to be arrested than fascists. The police justified this by interpreting anti-fascist activity as aggressive and thus, wittingly or not, acted as stewards for fascist meetings to ‘preserve the peace.’”4 While antisemitism, and even fascist sympathies, among law enforcement certainly played a part in police actions, “the police were never convinced that the Group was apolitical and not secretly communist. Consequently, like their communist allies, the anti-fascist ex-servicemen were seen as radical agitators desperate to overturn the status quo.”5

If the modern history of militant antifascism typically takes the 43 Group as its point of departure, it is because the Group took on the three-way fight against both system-oppositional far-right and fascist groups and law enforcement (or more broadly, the repressive apparatus of bourgeois class rule). This three-way fight would be familiar to antifascists out in the streets of North America (and elsewhere) over the last five years, but the volatile events of the last year during the pandemic show that the political co-ordinates of struggle are both volatile and subject to rapid change. In my view, Derbent offers us a window into a particularly important moment—the struggle between the KPD and the German Social Democratic Party (SPD) during the rise of the Nazi Party—from a theoretically fruitful angle.

There is a temptation when revisiting the failures of the KPD and SPD as the Nazis ascended to political power to relitigate their ideological debates in order to settle political scores. It may be impossible not to belie one’s commitments when analyzing these failures. Derbent, for his part, takes a critical approach to the KPD’s political line by contextualizing it via social antagonism. He writes:

The communist leadership believed that the antifascist struggle involved the elimination of social-democratic influence in the proletariat, because this influence distanced the class from a genuine antifascist and anti-capitalist struggle. This analysis had two premises. The first—erroneous—was the widespread idea at the time that the Nazi movement would not withstand the test of power, that it would crack both because of the workers’ opposition and because of its internal contradictions. But the second premise of the KPD’s analysis was correct: the will to fight Hitlerism was totally lacking in social democracy. The SPD’s legalism led it to fight the communists rather than the Nazis.

On this basis, Derbent analyzes two related political lines held by the KPD in the run up to the Nazis taking power in 1933: first, the “third period” policy which held that socialists were “social fascists,” that is, social democrats functioned as a moderate wing of fascism, allied with the bourgeoisie against communism; and second, the two-front struggle of the “united front at the base,” which consisted of fighting socialist leadership and organizations while building alliances with SPD rank and file.

We will begin with the latter: as Derbent notes, the united front at the base policy resulted in an ambivalent political position: “The KPD could do or not do anything; it served ‘objectively’ either the Social Democrats or the Nazis.” It led, infamously, to the KPD’s participation in a Nazi-inspired referendum against the social-democratic government in Prussia in 1931. Derbent hints at the internal struggles within the KPD when deciding these policies, but does not underline the policies that resulted in the failures of the united front at the base. Here, I find Nicos Poulantzas’s verdict persuasive: the KPD relied on “electoral struggle as the favoured form of ‘mass action.’”6 At the same time, he adduces evidence that the KPD failed to set up united front organizations which could cement alliances between communists and the rank and file of the social democrats.7

Part of the failure of the united front from the base policy can be placed on the line that socialists were social fascists. Derbent departs from the typical reception of this part of the third period line. Some critics relegate the third period to the Stalinization of the Comintern, where “Moscow politics often influenced continental anti-fascist strategy more than Italian or German realities”—but this emphasizes external factors over contradictions internal to these “German realities.”8 By contrast, Derbent argues that the social fascist line was validated by the fact that social democrats repeatedly used the repressive state apparatus to quell communist organizing. The failure of the KPD and the SPD to align against the Nazis was not merely ideological, but also driven by antagonism between communist insurrectionism and the SPD, which presided at the helm of the repressive state apparatus. The socialist adherence of legalism, which brought repressive state power to bear on communist organizing also put them at odds with cadre on the ground who sought a more militant line for the Iron Front, the SPD’s antifascist fighting organization.9 Yet communists failed to seize the opportunity. As Poulantzas writes:

As far as the line itself is concerned, the inclusive designation of social democracy and the social-democratic trade unions as social fascist and as the main enemy, bore heavy responsibility for the failure of the united front. This was not so much because of the refusal of all contact between the leaderships, and even between the secondary ranks; it was particularly because of the policy toward the social-democratic masses, considered ‘lost’ as long as they were under the influence of social democracy… Even apart from the fact that the KPD’s main activity was still directed against social democracy, this activity was conceived of as a struggle between ‘organizations,’ not as mass struggle on a mass line.10

Though the KPD sought to form a united front with social-democratic workers in principle, they failed to translate this into practice. The “social fascist” label, in my view, is a symbol of this failure to build a mass struggle around a united front, and it lives on as an inflammatory epithet, largely doing the same work today. Nonetheless, what I have tried to excavate, via Derbent, is how, at the time, this misguided terminology reflected—in a partial way—social realities on the ground. While socialists and communists had a common enemy, organizationally they occupied structurally different social positions: one commanded state power and the other’s insurrectionary strategy was repeatedly quashed by the repressive state apparatus. But the KPD also failed to focus on the struggle beyond these organizational parameters. We must underline this kernel of truth while dispensing with the husk, which belies how communists underestimated the strength of emerging threat of fascism.

Toward a Contemporary United Front

It might seem that we are far from discussing the praxis of a contemporary united front. On the contrary. I have attempted to outline—and have perhaps belabored—the various points of antagonism between the SPD and the KPD in order to anticipate a series of ideological and structural pressures that militant antifascists could face during the Biden administration.

If we remove the historical labels and replace them with contemporary terms, these pressures will become more obvious. Given that militant antifascist groups today tend to organize around a united front policy, the differences between socialists, anarchists or Marxists is not nearly as profound as the split between militant antifascism and liberal antifascism.

Militant antifascism upholds the diversity of tactics to combat far-right and fascist organizing, organizes as a form of community self-defense which (at least ideally) builds reciprocal relationships with marginalized and oppressed communities, while recognizing the “revolutionary horizon” of antifascist struggle: fascism cannot be permanently defeated until the conditions which give rise to fascism are overthrown. (Depending on the context, as we will see below, other conditions might be present, such as settler colonialism).

Liberal antifascism, in Mark Bray’s concise definition, entails “a faith in the inherent power of the public sphere to filter out fascist ideas, and in the institutions of government to forestall the advancement of fascist politics.”11 Liberal antifascists appeal to the democratic norms of these institutions, but also assume that law enforcement will apply force to repress the fascism when it constitutes a legitimate threat; they also often appeal to the converse of this position: if law enforcement doesn’t intervene, then no legitimate threat is present.

While militant antifascism is best known for the embrace of the diversity of tactics, over the past several years many antifascists have worked to create a broader social atmosphere of everyday antifascism. Fostering everyday antifascism makes it possible to organize a broader movement which would challenge far-right groups when they mobilized in various cities across North America. Everyday antifascism could, under the right conditions, bring larger crowds to counter-protests; it also provides political education on how the seemingly small things, like seating far-right groups at restaurants or providing lodging, enabled the far-right threat to communities. With Trump in office there was no chance that antifascism could be funneled back toward an affirmation of American civic participation.

A Biden administration poses different problems. In August 2017, only a few weeks after the Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville, Biden published an editorial in The Atlantic denouncing Trump’s equivocations about the far right; he also referenced Charlottesville repeatedly during his campaign. In and of themselves, these denunciations didn’t drive his electoral messaging. But in light of the far-right raid on the Capitol,12 and the popular outrage which also accompanied this action, Biden is positioned to siphon parts of the broader atmosphere of everyday antifascism—which previously made it possible to organize militant antifascist actions relatively openly—to fortify Democratic voting coalitions. This co-optation of a weak sense of even liberal antifascist sentiment will drive the narrative that fascism, encapsulated and isolated as so-called “Trumpism,” was defeated with the victory and inauguration of the Biden administration, when in fact the far-right was diverted from system-loyal tendencies aligning with Trump and the Republican Party back toward system-oppositional forms of organization.

If this occurs, the Biden administration can work to legitimate liberal currents of antifascism while delegitimating—while applying the force of the repressive state apparatus toward—militant currents. If liberal antifascism succeeds in pulling everyday antifascism back toward forms of bourgeois forms of institutional cultural power, it will effectively empty everyday antifascism of any concrete political and organizational content, while setting the stage for state repression of militant antifascists.13 Any extension of law enforcement powers that follow in the wake of far-right actions related to the Capitol riot will redound against left-wing militants. What liberals will portray as the intransigence of militant antifascists will appear to them as an ideological victory, but it will be won with repressive state violence, dismantling militant antifascist organizations and undermining community self-defense.

The foregoing scenario is far from a fait accompli. It can be forestalled by renewed efforts at militant political education and organizing around a united front policy. The defeat of the Trump administration has untethered far-right organizing from its system-loyal pretensions, though without necessarily undermining alliances forged by the mutual opposition of some far-right groups and police departments to the antipolice uprising of 2020. I will conclude by proposing a series of theses concerning a united front policy for militant antifascists in North America, though I believe some points would also hold in other situations. I defend them in more detail elsewhere.14 We will begin with defining two terms: fascism and the far right.

1. Fascism is a social movement involving a relatively autonomous and insurgent (potentially) mass base, driven by an authoritarian vision of collective rebirth, that challenges bourgeois institutional and cultural power, while re-entrenching economic and social hierarchies.

This definition of fascism—adapted from the work of Matthew N. Lyons and drawing from the discussion between Don Hamerquist and J. Sakai in Confronting Fascism (2002)—is a marked departure from the most common Marxist definition, which holds that fascism is “the open terrorist dictatorship of the most reactionary, most chauvinistic and most imperialist elements of finance capital.”15 Whereas Dimitrov’s formulation, as it is typically applied, treats fascists in the streets as instruments of the most reactionary faction of capital, the definition I offer asserts that fascist social movements are relatively autonomous formations that challenge bourgeois institutional and cultural power. This autonomy does not preclude hegemonic formations between fascists and the bourgeoisie. As Hamerquist argues, the Nazis’ seizure of power united factions of the ruling-class interested in imposing fascism “from above” with non-socialist factions (and I’m using the term “socialist” as loosely as possible here) of the fascist movement and “nazi political structure had a clear and substantial autonomy from the capitalist class and the strength to impose certain positions on that class.”16

As to the class composition of fascism, Derbent comments that “workers were the only social group whose percentage of Nazi party members was lower than its percentage in the total population.”17 Closer to the present, an examination of 49 of 107 persons arrested for participation in the Capitol riot indicates the generally petty bourgeois character of participants.18 Both observations affirm that the class composition of the far right and fascism is more complex than the most reactionary faction(s) of the bourgeoisie. In North America, the far right draws from elements of the white petty bourgeoisie who are seeking to protect their social status—purchased, as W. E. B. Du Bois argues, through the wages of whiteness—and/or their class position. Fascism is, in my view, relatively autonomous because it is anti-bourgeois, but anti-capitalist only to the degree that it seeks to reorganize capital accumulation on terms conducive to its base.

2. Fascist ideology and organizing develops within a broader far-right ecological niche.

Lyons defines the far-right as inclusive of “political forces that (a) regard human inequality as natural, inevitable, or desirable and (b) reject the legitimacy of the established political system.”19 Lyons’ definition focuses our attention on two key features of the far-right milieu, within which fascists organize. First, far-right groups seek to re-entrench social and economic inequalities, but the social hierarchies they advocate aren’t necessarily drawn along racial lines. Lyons gives the example of the Christian far right, which advocates for a theocratic state that centers heterosexual male dominance. In general, this movement has embraced Islamophobia and “promotes policies that implicitly bolster racial oppression,” but some groups have conducted outreach to conservative Christians of color while others have formed alliances with white supremacist groups.20 Fascist movements emerge within a broader milieu of rightwing social movements and these various groups sometimes establish alliances and sometimes conflict. In fact, one purpose of antifascist counter-protesting when these groups rally is to put pressure on their organizing; when these rallies are disrupted or dispersed through antifascist action, far-right alliances often rapidly splinter as prominent figures and groups within the far right trade accusations and recriminations.

Second, far-right groups reject the legitimacy of, as I would phrase it, bourgeois-democratic institutions of political and cultural power. Though mainstream conservativism has been pulled toward the far-right in ideological terms, organizational differences between “oppositional and system-loyal rightists is more significant than ideological differences about race, religion, economics, or other factors.”21

3. Militant antifascism is involved in a three-way fight against insurgent far-right movements and bourgeois democracy (or, in ideological terms, liberalism).

More precisely, each “corner” of the three-way fight struggles against the other two at the same time this struggle offers lines of adjacency against a common enemy. The first and most fundamental lesson of the three-way fight is that while both revolutionary movements and far-right movements are insurgent forms of opposition against bourgeois democracy, “my enemy’s enemy is not my friend.” Given that far-right groups also aim to recruit or ally with some revolutionary leftist groups, it is all the more important to root out all forms of chauvinism within our practices and organizations. Second, we must recognize the line of adjacency between militant antifascism and the egalitarian aspirations of bourgeois democracy. It is the shared appeal to egalitarianism which makes fostering a broader sense of everyday antifascism possible. But it also means, as I will argue in thesis six, that militants must uphold a revolutionary horizon to keep the limitations of liberal antifascism in focus.

We will deal with the line of adjacency between the far right and bourgeois democracy (or liberalism) in the next two theses. But before moving on, we must examine the relationship between far-right groups and law enforcement. The slogan that “cops and klan go hand-in-hand” expresses two fundamental aspects of this relationship. First, it acknowledges the systemic role of law enforcement: that is, law enforcement protects the systemic white supremacy of North American settler-colonial states. Second, it also emphasizes not only common membership between the two groups (when police, for example, are also members of the KKK), but also the ideological bases, through which police and system-loyal vigilante groups find common cause in opposition to leftist movements. However, it would be incorrect to assume that there are no antagonisms between law enforcement and far-right groups. In my view, it is more accurate to differentiate between what I would call system-loyal vigilantism and system-oppositional armed organization. On the terms established by Lyons, all far-right groups are ideologically system-oppositional, but not all of them are organized in system-oppositional forms. Over the last few years, many framed their actions as system-loyal vigilantism, which I would define as the use of violent tactics to harass, intimidate, or physically harm individuals or groups participating in transformative egalitarian movements. While some levels of law enforcement tend to be permissive or deferential toward system-loyal rightwing vigilantism, at least at the federal level, law enforcement has moved to repress system-oppositional groups organized around armed insurgency. In 2020 alone, police moved to incapacitate numerous far-right armed accelerationist groups, including members of The Base, Atomwaffen, and the more loosely-affiliated boogaloo movement. We must not mistake law enforcement repression to signal an unequivocal antagonism between police and the far right or any degree of common cause between these targeted far-right groups and militant and revolutionary leftist movements.

4. The particularity of the three-way fight is dependent on concrete social relations. Far-right and fascist groups draw on and respond differently to different social contexts. For example, during the interwar period, fascist movements drew from the imperialist aspirations of European nationalisms. In North America, far-right movements emerge in relation to broader ideological and material forms of settler-colonialism (which includes—meaning that capital accumulation is imbricated in—elements of white supremacy, heteropatriarchy, ableism, and Indigenous dispossession).

In North America, the historical development of liberal political and cultural institutions is inseparable from the development of settler-colonialism. Nonetheless it would be undialectical to treat them uncritically as the same thing. Instead, in my view, it is more precise to contend that settler-state hegemony is formed by the mediation of bourgeois liberalism and white supremacist settlerism. I would define white supremacist settlerism as an ideological framework which privileges both white entitlement to land (possession or dominion) over the colonized’s right to sovereignty and autonomy and entitlements encapsulated in what W. E. B. Du Bois called the “public and psychological wage of whiteness.” Examining the end of the Reconstruction period in the southern United States after the Civil War, Du Bois argues that the potential for the formation of abolition democracy, built on the solidarity between the black and white proletariat, was defeated by the hegemonic reorganization of settler-state hegemony which ensured forms of deference and the institutionalization of racial control as well as opening institutional access to education and social mobility to poor whites, drawing them, even if only aspirationally, into the petty bourgeoisie and labor aristocracy.22

Du Bois’ analysis remains the prototype—though it must be theoretically corrected by incorporating the role that the settlement of the western frontier played in this dynamic—for conceptualizing settler-state hegemony and the role that whiteness plays within it. The presidential campaigns of 2020, in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic and then the widespread antipolice uprising, offered two competing visions of reorganizing American settler-state hegemony—one which attempted to pull some system-oppositional far-right movements into system-loyalty and the other which took on a form of superficial antifascism—but it also demonstrated that a common interest in maintaining settler-state hegemony against challenges from the revolutionary left and the liberation struggles of oppressed peoples forms the basis of the line of adjacency between bourgeois liberalism and white supremacist settlerism.

5. Far-right movements are system-loyal when they perceive that the entitlements of white supremacy can be advanced within bourgeois or democratic institutions and they become insurgent when they perceive that these entitlements cannot.

In the first thesis, I stated that fascist groups appeal to an authoritarian vision of collective rebirth. In North American settler-colonial societies, far-right and fascist groups demand the re-entrenchment of the social and economic hierarchies which enabled white social and economic mobility; they perceive that their social standing is in jeopardy and demand that settler-state hegemony be tilted “back” toward their advantage. In sum, far right movements assert supposed “rights” of white settlerism which supersede the formal guarantees and protections granted through the liberal institutions of settler-state hegemony.

I would suggest that liberalism and white settlerism were historically able to coexist because the latter’s interests did not interfere with the former’s. Fascism failed to emerge as a profound challenge to American political hegemony in the 1930s and 1940s because, as Sakai notes, “white settler colonialism and fascism occupy the same ecological niche. Having one, capitalist society didn’t yet need the other.”23 In the 1950s to the 1970s, a variety of civil rights and liberation movements levelled a profound challenge to settler-state hegemony. Liberalism accommodated challenges from social justice movements by extending formal legal protections to marginalized groups and introducing new patterns of economic redistribution (social welfare). This did not overturn the expectations and entitlements of the wages of whiteness. As Cheryl Harris contends, “after legalized segregation was overturned, whiteness as property evolved into a more modern form through the law’s ratification of the settled expectations of relative white privilege as a legitimate and natural baseline.24” In other words, white entitlements would be codified into law as long as they could be framed in supposedly color blind terms—but these color-blind terms would also contribute to the (incorrect) perception that systematic white supremacy has been pushed to the margins of American society.

As recent events reveal, settler-state hegemony is not immune to crisis. As Marx and Engels argue in The Communist Manifesto, the social position of the petty bourgeoisie is always tenuous because “their diminutive capital does not suffice for the scale on which Modern Industry is carried on.”25 While the white petty bourgeoisie has repeatedly been “bought off” by social mobility or access to land (available due to Indigenous dispossession), even during the period of neoliberal policy, that does not mean that settler-state hegemony will continue to reorganize future hegemonic blocs successfully. The threat remains that an insurgent fascist movement, organized around the rebirth of the settler-colonial project, will fill that hegemonic vacuum.

6. A revolutionary horizon is a necessary component to antifascist organizing; that is, there is no meaningful way in which fascism can be permanently defeated without overthrowing the conditions which give rise to it: capitalism and white supremacy, and in North America, settler-colonialism.

Militant antifascism is organized in order to meet the imminent threat of fascist organizing; it is an instantiation of community self-defense. A united front is necessary in situations where the revolutionary left is present but lacks a mass base, but it is always caught in a contradiction: the major leftist ideological currents—socialism, anarchism, and communism—converge in a united front but diverge around the particulars of the revolutionary horizon. While combatting fascism is the immediate task of militant antifascism, antifascists must maintain a revolutionary horizon, even if only in broad outline, in order to avoid being absorbed within the ideological parameters of liberal antifascism. At the same time, militants must also recognize that antifascist work cannot merely be absorbed into revolutionary work; antifascism is community self-defense.

7. Militant antifascism must uphold the diversity of tactics.

From a practical perspective, militant antifascism is distinguished from liberal antifascism by a willingness to use the diversity of tactics, up to and including physical confrontation, to disrupt far-right organizing. Effective militant organizing, though, must not transform the diversity of tactics into merely physical confrontation.26 Antifascism seeks to raise the cost of fascist organizing and that is the most obvious reason that the diversity of tactics plays an important role in organizing. As Robert F. Williams observed in 1962, racists “are most vicious and violent when they can practice violence with impunity.”27 Physical confrontation raises the stakes of fascist attempts to harass and intimidate communities as they organize. But it is important to emphasize that physical confrontation still tends to come late in practice: antifascists conduct research and publicize the fascist threat and dox fascists, we put pressure on supposedly community-accountable institutions to deplatform or no-platform far-right groups, when fascists rally we meet them in the streets to disrupt their actions. Militants uphold the importance of the diversity of tactics but that doesn’t mean, against popular conceptions, that violence is necessary. The critical question is always: which tactic can cause the greatest disruption to far-right movements at each stage of organizing?

Events of the last year especially have revealed the weaknesses of liberal mechanisms to stem far-right organizing. For years, liberal antifascists interpreted the lack of law enforcement pressure against the far-right as a lack of urgent threat, and when the potential scope far-right violence erupted into popular consciousness on January 6th, 2021, it was years too late. The failure of far-right and fascist groups to undermine the transition of government power was due not to police repression (in fact, there was a distinct absence of police repression on that particular day), but primarily to internal organizational weaknesses, which I would attribute in part to pressure brought to bear on these groups over the last five years of antifascist organizing.

When confronted with emerging far-right movements, and unlike liberal antifascists, militant antifascists act sooner so that we don’t have to take greater risks later. Antifascists must maintain a revolutionary horizon, but at the same time remain focused on the immediate threat of fascist organizing. A world where fascists can openly organize is worse than one where they cannot.

Derbent’s book testifies to the contributions and sacrifices made by German communist antifascists until a much more overwhelming military response deposed fascism from political power. Though German fascism and Italian fascism were historically defeated in 1945, it will take a greater effort to defeat fascism once and for all. Part of that work must be done now by a united front of militant antifascists.

Endnotes

1 In Categories of Revolutionary Military Policy, Derbent argues that European communist parties failed to defeat Nazi invasion due to their organization as “primarily legal parties supplemented by clandestine military structures” (5); on his account, they were more effective when improvising practices of protracted people’s war. It would have been interesting to see this argument integrated in the present volume.

2 See, for example, Mark Bray, Antifa: The Anti-Fascist Handbook (New York: Melville House, 2017), 39 ff.

3 This specific phrasing is from one of the Group’s pamphlets, quoted in Daniel Sonabend, We Fight Fascists: The 43 Group and Their Forgotten Battle for Post-war Britain (London: Verso, 2019), 72.

4 M. Testa, Militant Anti-fascism: A Hundred Years of Resistance (Oakland: AK Press, 2015), 150.

5 Sonabend, We Fight Fascists, 119.

6 Nicos Poulantzas, Fascism and Dictatorship: The Third International and the Problem of Fascism. Trans. Judith White (London: Verso, 1979), 184.

7 Poulantzas, Fascism and Dictatorship, 182.

8 Bray, Antifa, 20.

9 Bray, Antifa, 23–24.

10 Poulantzas, Fascism and Dictatorship, 182 (my emphasis).

11 Bray, Antifa, 172.

12 In January 2021, supporters of US president Donald Trump broke into the US Capitol building, resulting in several deaths and members of Congress fleeing the building.—Ed.

13 As Matthew N. Lyons, notes, “repression…can even come in the name of antifascism, as when the Roosevelt administration used the war against the Axis powers to justify strikebreaking and the mass imprisonment of Japanese Americans.” See Insurgent Supremacists: The U.S. Far Right’s Challenge to State and Empire. Montreal: Kersplebedeb, 2018), ix.

14 See Philosophy of Antifascism: Punching Nazis and Fighting White Supremacy (London: Rowman and Littlefield International, 2020); “Between System-Loyal Vigilantism and System-Oppositional Violence,” Three Way Fight (October 25, 2020) [http://threewayfight.blogspot.com/2020/10/between-system-loyal-vigilantism-and.html]

15 George Dimitrov, The Fascist Offensive & Unity of the Working Class (Paris: FLP, 2020), 4.

16 Hamerquist, Don. [2002]. “Fascism and Anti-Fascism,” in Hamerquist et al. Confronting Fascism: Discussion Documents for a Militant Movement. 2nd edition. (Montreal: Kersplebedeb, 2017), 41. Hamerquist argues, for example, that Fascist labor policy under the Nazis extended beyond “the genocidal aspect of continuing primitive accumulation that is part of ‘normal’ capitalist development…The German policy was the genocidal obliteration of already developed sections of the European working classes and the deliberate disruption of the social reproduction of labor in those sectors—all in the interests of a racialist demand for ‘living space’” (43).

17 Despite the repeated assertions by paternalistic liberals that fascism is a working class movement, even liberal historians acknowledge that workers “were always proportionally fewer than their share in the population.” See Robert O. Paxton, The Anatomy of Fascism (New York: Vintage, 2004), 50.

18 Lambert Strether, “The Class Composition of the Capitol Rioters (First Cut), Naked Capitalism, January 18, 2021 [https://www.nakedcapitalism.com/2021/01/the-class-composition-of-the-capitol-rioters-first-cut.html]

19 Lyons, Insurgent Supremacists, ii.

20 Lyons, Insurgent Supremacists, 28.

21 Lyons, Insurgent Supremacists, ii.

22 W.E.B. Du Bois, Black Reconstruction in America: An Essay Toward a History of the Part Which Black Folk Played in the Attempt to Reconstruct Democracy in America, 1860–1880. Ed. Henry Louis Gates, Jr. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007), 573–574.

23 Sakai, “The Shock of Recognition,” in Confronting Fascism, 130.

24 Cheryl Harris, “Whiteness as Property,” Harvard Law Review 106, no. 8 (June 1993), 1714.

25 K. Marx and F. Engels, Manifesto of the Communist Party & Principles of Communism, (Paris: FLP, 2020), 41.

26 Indeed, Petronella Lee contends, in a point that applies both to the creation of a broader antifascist culture and to the use of the diversity of tactics, that “we cannot focus almost exclusively on physical activities and/or traditionally male-dominated spaces. It’s important to have spaces, roles, and activities that account for the variety of diversity of social life—for example considering things like ability and age.” Nor should we perpetuate gender stereotypes in organizing community self-defense. See Anti-Fascism against Machismo (Hamilton: The Tower In Print, 2019), 36.

27 Robert F. Williams, Negroes with Guns (Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 1998), 4.